Facial Nerve Palsy

Causes

Facial nerve palsy can occur from a variety of causes. It can be present at birth due to a developmental issue or it can occur from a number of acquired conditions. From birth, it can also occasionally be associated with a syndrome. There are approximately 50 known causes of facial palsy with the most common being due to Bell’s palsy which is thought to be caused by a viral infection. This can occur in both children and adults. Another main cause in children is developmental or congenital facial palsy where the child is born with a facial palsy. Some of the causes are listed below.

Congential

- Developmental

- Moebius Syndrome

Acquired

Infectious

- Bells Palsy

- Middle Ear Infections

- Ramsay Hunt

- Leprosy

Metabolic

- Diabetes

- Hyperthyroidism

Neoplastic

- Brain tumour

- Schwannoma

- Parotid Malignancy

- Cholesteotoma

Neurologic

- Guillain-Barre

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Myasthemia Gravis

- Iatrogenic

- Birth Trauma

Surgery

- Acoustic Neuroma

- Parotid Gland

Traumatic

- Fractured Base of Skull

- Penetrating wounds to face

Anatomy

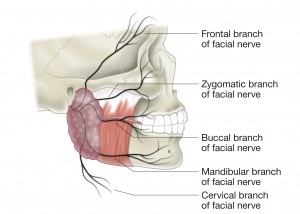

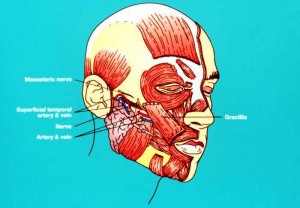

The anatomy of the facial nerve and its course from the brain stem to the muscles of the face is complex taking a circuitous route through the skull (temporal bone) and the middle ear. It exits the skull and the passes into the parotid gland where it divides into its 5 main branches (Fig 1). From there it passes into the forward dividing more into its individual muscular branches. Besides having nerve fibres for the muscles of facial expression it also has nerve fibres for taste buds in the tongue, salivary and lacrimal gland (tear) function.

Clinical

Interruption of the nerve anywhere along its length will result in a facial palsy. The site and cause of the interruption will then dictate the symptoms and signs that each patient will have. The signs and symptoms will then lead the treating physician to a potential number of investigations to ascertain what is causing the facial palsy.

These investigations may include tests to measure the function of the lacrimal gland (tear production), salivary glands or taste to the tongue. Hearing tests and nerve conduction and electromyographic studies may also be required. Radiological imaging with CT scans and MRI scans are commonly done in the investigation of someone with facial palsy.

Management

The management of facial palsy is determined by the cause of the palsy and the duration of it being present. The management needs to address the cause of the facial palsy as well as treat the effects resulting from the facial palsy. There are types of facial palsy that can recover and others that will not recover. The commonest type of palsy that recovers is a Bell’s palsy, where as a developmental facial palsy, which a child is born with, usually is permanent. In the management of Bell’s palsy it is common to be prescribed steroids to help reduce the swelling of the facial nerve and antiviral medication.

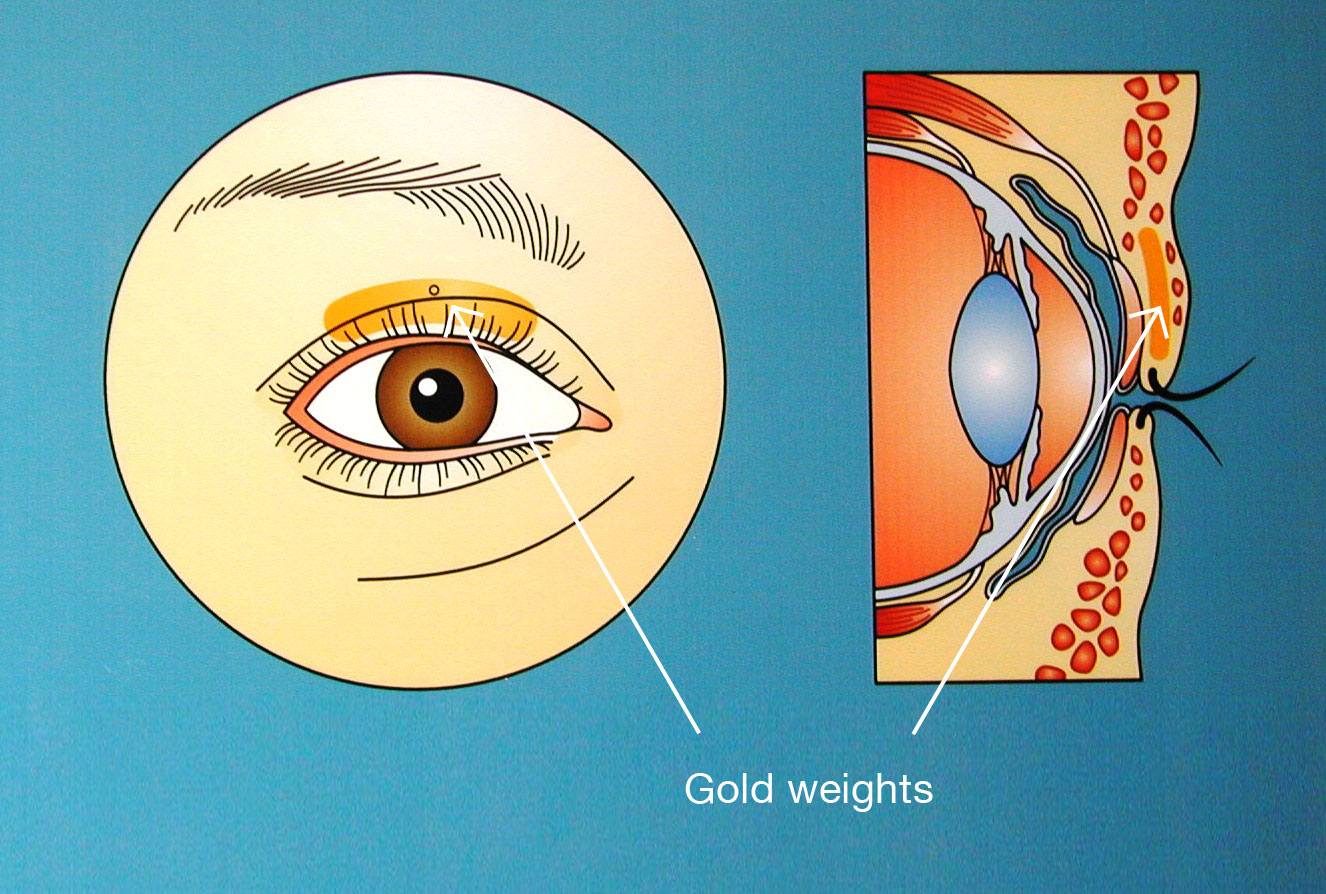

The resultant facial palsy will affect the face in two ways. The first is a loss of sphincter function round the eye, mouth and nose with the second being facial asymmetry. Both of these can be very distressing to the patient. Eye protection is paramount so that no damage occurs to the front of the eye (cornea) due to the loss of blink and eye closure. This can be managed with eye drops and lubricants, taping the eye shut at night and a variety of surgical procedures including tarsorraphy or insertion of gold weights (Fig 2) or other devices to improve blink.

When a facial palsy will not recover then the duration of the palsy determines the management. Muscles that lose their nerve supply lose their ability to function in approximately 18 months to 2 years. So if the patient presents prior to this time frame it may be possible to use a new nerve supply to make the facial muscles function again. This would be through utilising nerve grafting or nerve transfer procedures. If the patient presents later then a number of other surgical options maybe required.

The aims of surgery for reconstruction of facial palsy are to restore facial harmony, protect the eye, provide symmetry of the face at rest and with expression with minimal unwanted motion (synkinesis).

Facial Palsy Reconstruction

Early surgical options

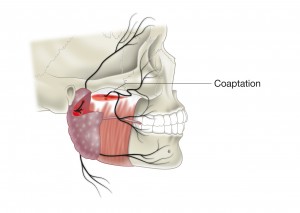

In patients who have had an injury to the facial nerve through an accident such as a laceration to the face, head injury with a fractured base of skull or surgical division of the nerve in tumour surgery and they present with a year of the injury then nerve grafts and nerve transfers are options available to them. These procedures provide new nerve fibres to the muscles of facial expression and restore motion to the face. These options include cross facial nerve grafts, masseteric nerve transfer (Fig 3) and hypoglossal nerve transfers.

Late surgical options

There are two groups of procedures for patients who present with a congenital palsy or an established long term facial palsy. These two groups are static procedures aimed at improving symmetry without providing motion and dynamic procedures that provide facial motion.

Static procedures

For eye protection include:

- Gold weight insertion in the upper eyelid (Fig 2)

- Tarsorraphy (partially joining the eyelids together)

- Palpebral springs.

For restoration of facial symmetry at rest include:

- Nerve / facial muscle excisions

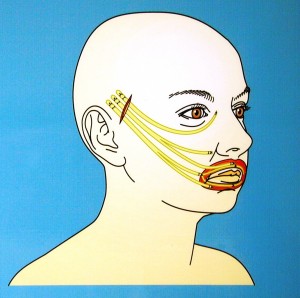

- Facial slings – These types of procedures include Tendon or fascial slings to lift up the paralysed face to minimise facial droop (Fig 4).

- Brow, Face and Neck lifting procedures (Fig 5) to restore facial position at rest.

Dynamic Procedures

For restoration of smile. Muscle transfer procedures.

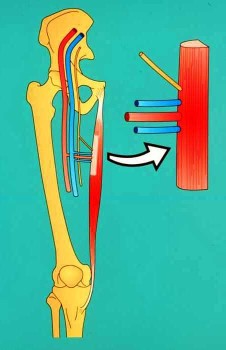

The mainstay of facial reanimation for long term and congenital types of facial palsy are procedures known as free vascularised muscle transfers where new muscles and nerves are inserted into the paralysed face to restore facial motion. The most common muscle used for this is the gracilis muscle in the upper inner thigh, which is an expendable muscle (Fig 6).

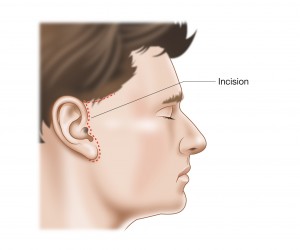

A portion of the muscle is taken from the leg with its own nerve and blood vessels and transferred into the face to recreate smile with upper lip elevation. The muscle is inserted into the face through a facelift style incision and then the blood supply to this new muscle is reconnected to the blood vessels in the face with the use of routine microsurgery.

The nerve supply to the new muscle is then connected to a new nerve either by a cross facial nerve graft or to the masseteric nerve in a two stage or one stage procedure schematically demonstrated in Fig 7.